Central and Eastern Europe face an erosion of democracy

The EU fails to curb growing populism and corruption

20 February, 21:18(ANSA) - TRIESTE, 20 FEB - After twenty years of democratic consolidation, the post-socialist Europe is undergoing a widespread crisis ''in'' democracy, which resulted in a real crisis ''of'' democracy in Hungary and Poland.

Hungarian political scientist Béla Greskovits explained that, on the one hand, this area of Europe facing an erosion of democracy, or a general decline in the involvement of civil society in the practices of democracy: low turnout, lack oif party identification. On the other hand, there is a ''setback'' that, according to Greskovits, implies both the radicalization of groups within the politically active population, and the partial rejection of democratic principles by the elite. The decline indicates a crisis ''of'' democracy.

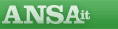

Hungary and Poland are often cited by political scientists as examples of democratic deconsolidation. Both show that populist parties, once they are ruling, have a limited number of options to fulfill their election promises. A feasible way is to combine policies that respond to voters' will (restrictive measures for immigrants, taxes on corporations, containment of welfare programs etc.) with measures to limit public scrutiny and political competition.

Clear examples of authoritarianism are the facts that the Alliance of Young Democrats (Fidesz) in Hungary has rewritten the constitution, removing much of the democratic controls, and Law and Justice (PiS) in Poland has limited the authority of the Constitutional Court and pu public Ministries and the public television under government control.

However, the setback for democracy does not need blatantly anti-democratic measures, but can express itself through the degradation of justice, lack of independent media, a little transparent electoral process and so on. In all these areas, the deterioration is self-evident to everybody in Central and Eastern Europe, generating massive protests against the restriction of civil rights in Poland or against the decriminalisation of some offenses related to corruption and abuse of office in Romania.

The explanation for this result is due to the failure of basic ''anchors of democracy'', that stabilise and consolidate a political system such as the empowering function of political parties and the role of the European Union.

The problem with the EU is twofold. First: the economic constraints have created serious problems of legitimacy to their governments. On the one hand, austerity has narrowed the economic space and, in order not to be overwhelmed by the populists, the traditional parties had to adopt a nationalist, anti-capitalist and eurosceptic rhetoric.

On the other side, due to the crisis, most of the governments in office were prematurely ousted in the last seven or eight years: Borisov and Oresharski Bulgaria, Sanader in Croatia, Gyurcsany in Hungary, Godmanis in Latvia, Boc in Romania and Radiova Slovakia, Pahor and Jansa in Slovenia.

The second issue is that the EU's influence on the policies has been minimal: in addition to providing rules and and purely formal procedures in democracies of Central and Eastern Europe, the EU has failed to curb the rampant corruption and did not develop effective tools to counter the appropriation of the state by private interests.

The most worrying development is ''corporate broking'' within political parties: the process of privatisation, EU funds and public contracts have in fact created opportunities for collusion between governments and business elites.

Recent investigations have involved former prime ministers: Romanian Ponta, Czech Neas, Croatian Sanader and Slovene Jana. In Slovakia, the Gorilla scandal in public procurement has overturned the outcome of general election in 2012. In Hungary, corruption is so pervasive that some prominent personalities belonging to Fidesz began to openly criticise the sudden enrichment of their colleagues.

Unfortunately, the EU's ability to counter those coalition governments involved in the dismantling of institutional control ended up being woefully inadequate.

Recent judicial reversals (the trials against Sanader and former Mayor of Zagreb Bandic in Croatia, and against Jana and various so-called ''tajkuni'' in Slovenia were canceled, suspended or delayed), the insufficient guarantees offered to informants in political processes in Czech Republic and Slovakia, the low commitment to fighting against corruption in Bulgaria and Romania and a discredited judicial system in Latvia and Lithuania prove the growing gaps in the institutions in the former socialist countries.

In summary, the new member states of eastern Europe seem to be walking down a one-way-dead-end street. Erosion of democracy and setback further widen the gap between the electorate and the political parties. For this reason, elites are encouraged to continue their collusive activities.

The EU's inability to sanction such behaviour creates fertile ground for populist parties, whose strategy is to restrict civil and political freedoms in the implementation of their irresponsible plans.

(ANSA).