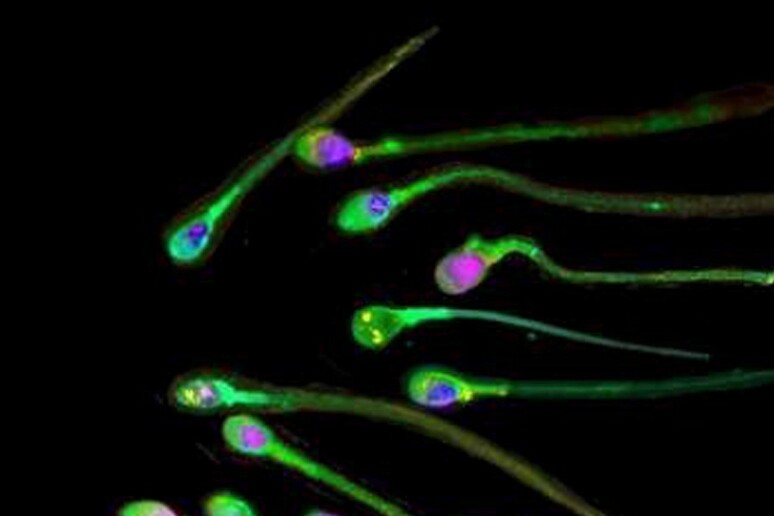

Cells 'disguised' as spermatozoids have managed to repeat the success of animal cloning experiments and, after many years of frustration, have managed to relaunch this research sector. This was made possible by a technique drawn up in Italy by a group from the University of Teramo under one of the pioneers of cloning research, Pasqualino Loi. Described in the magazine Cell Reports, the technique could be used both in the zootechnics field and to protect endangered species - from Marsican brown bears to Pyrenean chamois to the Sumatra rhinoceros. In zootechnics, cloning could help to select animals that show a higher resistance to certain factors, such as climate change. In the biomedical field, it could become possible to reproduce human diseases even in animals other than mice to study them in detail. The experiments on cloning conducted over the past 15 years consisted in extracting the nucleus - the central structure that contains the DNA - from a differentiated adult cell and transferring it into an ovary that had previously had its genetic material removed. The substances and signals that remained in the ovary were to have done the rest, stimulating the nucleus of the adult cell to go back in time to the point of transforming it into an infant, undifferentiated cell. "It was a path filled with difficulties: the clones had many defects and a high mortality rate," Loi noted. Between 1997 and 2015, only 1% of the animals were born, since "in millions of years of evolution, the ovum never received somatic cells. They had only received spermatozoids and knew how to deal with them." Loi's group sought an alternative and initial work was done by such scientists as Domenico Iuso and Marta Czernik, in collaboration with French and Polish research groups. "Ten years of work were needed," Loi added, "to force a differentiated somatic cell to become a spermatozoid." It became possible by transferring into an adult cell a protein called protamine, produced in the final phases of spermatozoid maturation. Introduced into the adult cell, the protein transformed the structure, giving it the lengthened characteristic of spermatozoid and making it possible to 'trick' the ovum and push it to reprogram the cell. "By applying this technique in vitro," Loi said, "we obtained double the number of embryos compared with that produced thus far with the traditional technique."

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED © Copyright ANSA